M V Satish,

Whole Time Director & Senior Executive Vice President (Buildings, Minerals & Metals)

We are in an industry where danger is always lurking round the corner and hence safety should be a second nature for every person working at a construction site. Upward, downward and horizontal communication must be quicker, easier and more prompt to not just enhance safety but productivity at sites as well. Communication is usually for a purpose, and unless that purpose is accomplished, the communication is not complete. Hence, kindly ensure that your communication is properly understood and acted upon!

While creating a safe work culture is all about doing the routine things right, our adoption of smart technologies and digitalization has given us an edge that we should not give up. I want all of you to integrate safety requirements in the way you do business in your respective domains. It is not an external fitting but just as important as anything else that we do at site and by following safety processes diligently, we can also ensure productivity and profitability.

FOR A SAFE VIEW FROM THE TOP

Addressing the danger of fall from heights

As India’s Prime Minister was inaugurating the world’s tallest statue, a group of people watching the show wondered how it would have felt for workmen to stand at the top of the Statue of Unity (SoU) when constructing the Sardar’s head. The perils of standing on a platform and working at heights of over 500 feet buffeted by a strong wind blowing down the Narmada river is something that many of us would baulk to even think about. Whether it is constructing a high rise tower or stringing a transmission line perched high up in the sky, erecting a humungous dome for an atomic plant or working on a bridge hanging over water and another bridge with ‘live’ traffic, workmen are exposed to the ever-present hazard of Fall from Height (FFH). “As we rise higher, so do the risks for our workforce and hence we need fool-proof safety strategies to prevent any untoward occurrence,” emphasizes P Nagarajan, who in his capacity as Head – EHS for B&F IC, is monitoring the implementation status of fall prevention at several high-rise projects. He is speaking with some confidence as B&F projects have won a slew of British Safety Council’s ‘Sword of Honour’ regarded the pinnacle of safety recognition but all businesses across L&T Construction have a good record of preventing FFH.

A bird’s eye view of workmen atop the world’s tallest statue

Understanding the animal

Globally, FFH is among the leading causes, some say 30%, of serious and fatal injuries for construction workers. Research attributes this to the dynamic, complex, temporary and transitory nature of the construction industry. FFH could occur when working on roofing, painting, plumbing, drywall or wall covering, carpentry, electrical tasks, installing sheets and the like. While studies reveal that FFH occurs most due to fall from scaffolds, it could also result from fall from ladders, roofs, statues, bridges, transmission towers, elevated platforms, through walkways, openings or fall from another level.

Accessing heights with a safety climbing screen

“Individual variables like their demography, attitude, knowledge levels, behaviour patterns, physical characteristics and health are key reasons for FFH.”

– M Kamarajan

Advisor – EHS, B&F IC

Climbing heights, hooked to life lines

“Hazardous activities expose workmen to FFH,” remarks M Kamarajan (MK), Advisor – EHS, B&F IC, “but individual variables like demography, attitude, knowledge levels, behaviour patterns, physical characteristics and health are key reasons for FFH.” It is common sense that obese or elderly people should not be allowed to work at heights, even with protective gear, but attitude and behaviour are softer, intangible aspects that are more difficult to address. Santhosh Bhaskar, EHS – Head, Project SoU, had the ordeal of taming workmen with no background in safety procedures to understand and accept his mandatory safety briefings before being allowed to climb the statue. “Often such labour chooses to ignore these training sessions spelling danger for all,” says Nagarajan, “but more serious is the attitude of some that “it cannot happen to me” that is really a recipe for disaster.” There is a strong co-relation between FFH and ‘behaviour’ that could either be due to carelessness, misjudgement or overconfidence or even triggered by overwork, sleep deprivation and/or work depression. “It is a hydra-headed issue,” concedes MK, “therefore ensuring use of the right PPE like full body harnesses, safety belts, personal fall arrest systems and safety nets, is really a basic but important first step.”

While remaining safe is to a large extent the individual’s responsibility, dangerous site conditions like unprotected walkways, incomplete guardrails, slippery or sloped surfaces, improper placement of scaffolds and ladders and insufficient lighting could cause incidents. “It is very important to monitor the amount of time workmen spend at height,” cautions Gopi Krishnan, EHS In-charge, Project ICC Towers, “and ensure that they return before they get too tired or disoriented.”

Creating a safe environment

B&F’s Crescent Bay project recently clocked 25 million safe man hours, the ICC Towers 15 million and ITC Pragati Towers 13 million safe man hours all of which were high-rise towers in Mumbai with some soaring to 60+ floors. “Apart from working at such heights, since our site is close to and facing the Arabian Sea, the wind is sometimes so strong that it threatens to just blow you away,” shares Gopi Krishnan. To combat both the threats of height and wind, the EHS team erected Safety Screens that created a sense for the workmen as if they were working at ground level. “It is a hydraulic climbing safety screen stretching across 3 levels that prevents the workmen to see the height at which they are working, keeps them safe from the buffeting winds and, most importantly, prevents them from falls.”

Creating a safe work environment at height

“Safety screen is a hydraulic climbing system stretching across 3 levels that prevents the workmen to see the height at which they are working, keeps them safe from the buffeting winds and, most importantly, prevents them from falls.”

– Gopi Krishnan

Manager – EHS, ICC Towers

At SoU, RSPs (Rope Suspended Platforms) were used for the bronze welding activity when the team found it next to impossible to rescue workmen from the vertical fall arrestor due to the outward slope of the statue’s external surface. Still inaccessible even by cranes, Bhaskar and team evolved a very simple solution of installing two RSPs close to each other at the same level of work to carry out the work that resulted in huge savings both in terms of money and lives. Where scaffolding was a nonstarter to reach the weld joints of the fingers of the statue, they resorted to a sway rope of 18 mm dia to drive the RSP up to the required height of 83 m.

Bhasker goes on to explain that the available void area was cleverly used to create an overhead safe working platform extending the full 6 m with catch nets that had to be subsequently taken off considering the welding activities involved on the stubs. Thanks to this platform, all 2nd level activities including heavy lifting, were safely carried out. “After the stub locations were identified, the pre-installed working and intermediate platforms were equipped with aluminium ladders and grab-rope assemblies. We had an additional platform with a lifting cage ready to be pressed into service in case of any emergency.” The lifting of the bronze panels was also risky, “for which we introduced additional chain pulley blocks to offset the cascading effect.”

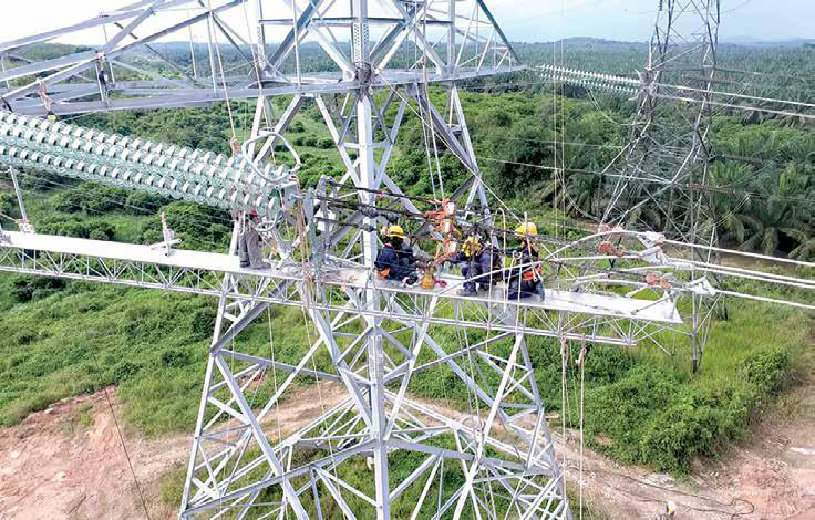

A safe platform on sag bridges for transmission tower erections

In PT&D, the safe environment was created by a sag bridge at one of the 168 tower locations across the 500 kV Yong Peng East Substation to Point A Transmission Line, Johor, Malaysia, on which safely perched 60 m above ground, a gang of 6 workmen went about their sagging works. “We introduced the sag bridge concept for the first time in West Malaysia in this project,” informs the EHS In-charge. “It is placed parallel with the rough sag of the conductor as a platform for fitters to carry out the final works while completely eliminating the hazards of working at height.” The advantage of this system is that it can be customized as per the tower specifications as was the case in this project. “A 20 m sag bridge was used to accommodate 5 m platforms in 4 parts with all tools required for final sagging placed on the bridge.” Communication is always vital in such tasks, he avers, “For reaching workmen positioned even higher, a special frequency walkie talkie was used to convey instructions while three types of signal systems were used to network with the crew: whistling is when the range of the tower is around 60 m high while instructions to commence or stop work are communicated by flagging from the ground level.”

“Every day, we lived with the threat of people falling off the edges, falling to the ground through openings, tripping into excavation pits or loose material falling on people working below; but being aware of these dangers is really half the battle won!”

– Santhosh Bhaskar

EHS In-charge, SOU Project

For teams from TI and Heavy Civil IC, building elevated corridors, bridges and barrages, the risk of FFH is a constant threat. The team from the recently completed Mandovi Bridge in Goa recall the perils of working over water and other full-functional, adjacent bridges with ‘live’ traffic streaming below them. Working atop each of the piers of the Medigadda Barrage was a test of the safety measures taken at site and the fact that the EHS In-charge, N Ramesh Kumar and team were able to clock 13.9 million plus safe man hours speak volumes of their success.

Capping a dome

Perhaps one of the best examples of working successfully at height was the first-of-its-kind effort to lift a 355t inner containment (IC) circular steel structure to a height of 44+m at the Kakrapar Atomic Power plant that obviated the need for workmen to be lifted many times to the top to fix individual panels, shares Sudharsan R, the then EHS Incharge. “We deployed an efficient 1350 T crane after ascertaining that its working load was 424 t, way above the intended lifting weight.” A special 18-holed spider, fabricated at site, was attached to the lifting hook of the crane and hooked to a spatial ring type truss, also fabricated in-situ. “We tested this set-up meticulously using concrete blocks,” explains Sudharsan, “and ensured the spatial truss was correctly aligned because the entire weight of the ring liner was distributed at 80 points from which they were hung using slings, load cells with online monitoring and adjustable shackles. ” Everyone involved in the exercise, signalmen, riggers, crane operators and welders, were trained thoroughly and then given different coloured (dress codes) to easily identify their respective trades on D-Day.

Rope suspended platforms at Project SoU

“As the first sequence, the hovering spatial ring was connected to the ring liner with slings and shackles and then,” Sudharsan pauses for effect, “on the proceed signal, the crane operator lifted the load to a minimum height, held it to ascertain stability before hoisting it to the prescribed height. Then it was lowered, positioned and then bolted securely by riggers on top of the structure.” Sudharsan adds how the wind was a crucial factor and the plan was to call off the lift if wind velocity exceeded 8 m/s or 29 km/hr.

Workmen fixing the individual panels of the prefabricated ring liner at Kakrapar Atomic Power Project

Making safe heavy lifts

Heavy lift erections are always critical tasks that call for a detailed staging plan depending on the weight and location of the lift. As per safe guidelines, such tasks are carried out either during lean hours, preferably late at night or in the early morning hours. While lifting precast and steel structures are common sights across infrastructure projects, the more complicated are the mammoth equipment across metallurgical and material handing projects requiring different safe approaches. There are comprehensive EHS schemes with a range of SOPs for various activities and digitalisation is making the process more secure.

At the JSW Dolvi project, MMH SBG achieved its heaviest lift of a 415 t (438 t considering the weight of both the rigging and hook block) converter using a 600 t Demag CC 2800-1 crane. Kausik Dutta, Head Construction Methods Planning Cell, shares that “With so many stake holders involved, all aspects of the lift had to be cross-checked multiple times in line with the rigging system guidelines and communicated precisely.” Another critical lift at the Dolvi site was the 300 t lower structure erection of Blast Furnace#2 and to minimize the risk of working at heights involving in-plane and out-of-plane inclinations, a detailed analysis backed with stability calculations was arrived at through a stage wise scheme that included horizontal lifting, upending to facilitate safe final erection.

“With so many stake holders involved, all aspects of the lift had to be cross-checked multiple times in line with the rigging system guidelines and communicated precisely.”

– Kaushik Datta

Head CMPC

Putting together a 52 t steel truss with a 35 m cantilever span across a 25,000- volt powerline passing beneath the span at Lucknow Metro Phase II is now considered a L&T safe benchmark for such daunting tasks. The entire construction method was driven through incremental push launching technique with five intermediate trestles using strand jacks, nosing trusses and counterweights. As the Railways had imposed a speed limit for the truss operations, the progress of the automatic launcher was slow, though steadily gaining around 500 mm in one go with the entire activity completed in 5 days.

Some blips

“Even with the best of intent and efforts, we still have a number of near misses,” acknowledges Nagarajan, “but rather than hiding them under the carpet, we record them diligently doing a thorough analysis to find out how it happened, what went wrong, what were the process faults and how can we prevent a repeat of that incident in future. We, at B&F, consider near-misses as great learning opportunities,” he declares.

“Every day, we lived with the threat of people falling off the edges, falling to the ground through openings, tripping into excavation pits or loose material falling on people working below; but being aware of these dangers is really half the battle won!” exclaims Bhasker who had his fair share of near misses and narrates one. “On 20th March 2018, during the erection of the structural frame at the 165 m level, a shim plate that was being used to increase the thickness of the beam broke away and fell as the erector was trying to remove the plates for further erection from the splice plate.” He stares at me as if reliving the incident. “Fortunately, since it fell into the designated exclusion zone at the 83 m level, no one was injured. We took immediate corrective action and such an incident never recurred.”

Ways to stay safe

A few other important boxes that EHS managers need to tick to prevent FFH:

- Professionals to set up scaffolds and ladders

- Safety monitoring systems like RFIDs in helmets that track the health of workmen

- Controlled access and ‘no-go zones’

- Railings, guard rails, surface protection like safety nets

- Work in groups or at least in pairs

Safe barricading for an elevated metro rail corridor

Are you healthy enough to work at height?

Full body harnesses and a check of all safety equipment before use are mandatory. “Perched on a platform, 500 feet above the ground is a bad place to find out that you suffer from vertigo,” says Bhaskar who even delivers humour with a deadpan expression. A workman’s fitness, vital signs like blood pressure, heart beats, pulse rates, fear of heights, claustrophobia, alertness and behaviour traits are all checked before he can climb. “In fact, we have introduced a biometric system in some of our sites,” says R Rajkumar, Digital Office, B&F, “so only authorized personnel can go up.”

How safety-conscious is the sub-contractor?

The sub-contractor is a very crucial cog in the wheel and his attitude to a large extent influences the attitude of his workforce towards safety. Often, EHS managers need to ‘manage’ errant sub-contractors which is undoubtedly tougher than influencing their workmen. “Yes,” nods Nagarajan, “the workmen of sub-contractors also need to be checked and their equipment certified and yes, all this is time consuming and often project managers are fretting about loss of productive time, but our response is that more time will be lost in case of an incident if the safety procedures are not followed to the ‘T’.”

“Finally, it is only training and more training that can save our day,” concludes MK.